Much talked about these days in the media, the unskilled-and-unaware phenomenon was mused upon since, as they say, immemorial times, but not actually seriously investigated until the ’80s. The phenomenon refers to the observation that incompetents overestimate their competence whereas the competent tend to underestimate their skill (see Bertrand Russell’s brilliant summary of it).

Although the phenomenon has gained popularity under the name of the “Dunning–Kruger effect”, it is my understanding that whereas the phenomenon refers to the above-mentioned observation, the effect refers to the cause of the phenomenon, namely that the exact same skills required to make one proficient in a domain are the same skills that allow one to judge proficiency. In the words of Kruger & Dunning (1999),

“those with limited knowledge in a domain suffer a dual burden: Not only do they reach mistaken conclusions and make regrettable errors, but their incompetence robs them of the ability to realize it” (p. 1132).

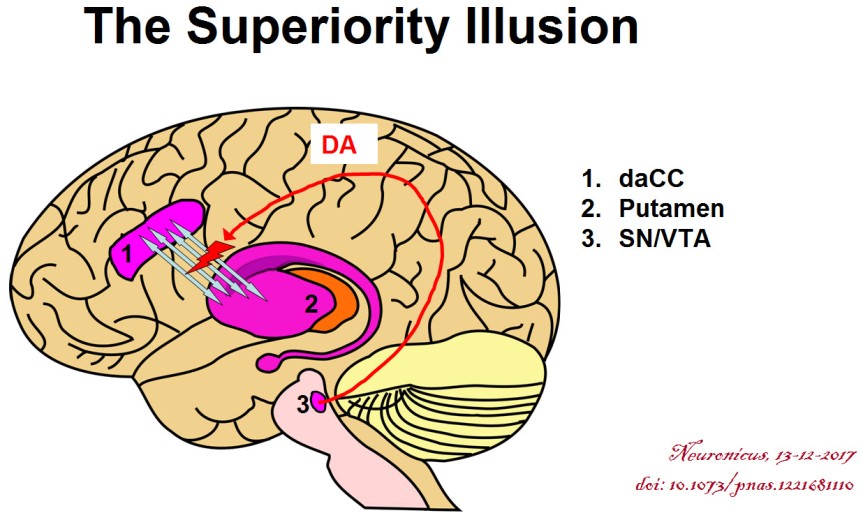

Today’s paper on the Dunning–Kruger effect is the third in the cognitive biases series (the first was on depressive realism and the second on the superiority illusion).

Kruger & Dunning (1999) took a look at incompetence with the eyes of well-trained psychologists. As usual, let’s start by defining the terms so we are on the same page. The authors tell us, albeit in a footnote on p. 1122, that:

1) incompetence is a “matter of degree and not one of absolutes. There is no categorical bright line that separates ‘competent’ individuals from ‘incompetent’ ones. Thus, when we speak of ‘incompetent’ individuals we mean people who are less competent than their peers”.

and 2) The study is on domain-specific incompetents. “We make no claim that they would be incompetent in any other domains, although many a colleague has pulled us aside to tell us a tale of a person they know who is ‘domain-general’ incompetent. Those people may exist, but they are not the focus of this research”.

That being clarified, the authors chose 3 domains where they believe “knowledge, wisdom, or savvy was crucial: humor, logical reasoning, and English grammar” (p.1122). I know that you, just like me, can hardly wait to see how they assessed humor. Hold your horses, we’ll get there.

The subjects were psychology students, the ubiquitous guinea pigs of most psychology studies since the discipline started to be taught in the universities. Some people in the field even declaim with more or less pathos that most psychological findings do not necessarily apply to the general population; instead, they are restricted to the self-selected group of undergrad psych majors. Just as the biologists know far more about the mouse genome and its maladies than about humans’, so do the psychologists know more about the inner workings of the psychology undergrad’s mind than, say, the average stay-at-home mom. But I digress, as usual.

The humor was assessed thusly: students were asked to rate on a scale from 1 to 11 the funniness of 30 jokes. Said jokes were previously rated by 8 professional comedians and that provided the reference scale. “Afterward, participants compared their ‘ability to recognize what’s funny’ with that of the average Cornell student by providing a percentile ranking. In this and in all subsequent studies, we explained that percentile rankings could range from 0 (I’m at the very bottom) to 50 (I’m exactly average) to 99 (I’m at the very top)” (p. 1123). Since the social ability to identify humor may be less rigorously amenable to quantification (despite comedians’ input, which did not achieve a high interrater reliability anyway) the authors chose a task that requires more intellectual muscles. Like logical reasoning, whose test consisted of 20 logical problems taken from a Law School Admission Test. Afterward the students estimated their general logical ability compared to their classmates and their test performance. Finally, another batch of students answered 20 grammar questions taken from the National Teacher Examination preparation guide.

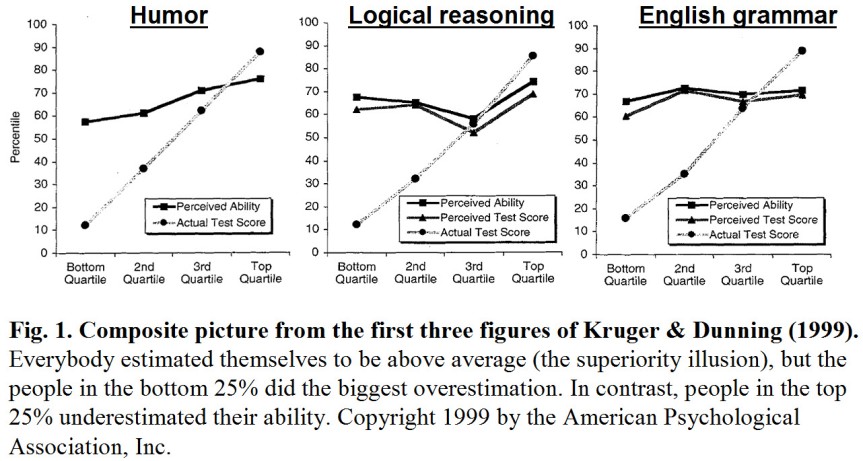

In all three tasks,

- Everybody thought they were above average, showing the superiority illusion.

- But the people in the bottom quartile (the lowest 25%) dubbed incompetents (or unskilled), overestimated their abilities the most, by approx. 50%. They were also unaware that, in fact, they scored the lowest.

- In contrast, people in the top quartile underestimated their competence, but not by the same degree as the bottom quartile, by about 10%-15% (see Fig. 1).

I wish the paper showed scatter-plots with a fitted regression line instead of the quartile graphs without error bars. So I can judge the data for myself. I mean everybody thought they are above average? Not a single one out of more than three hundred students thought they are kindda… meah? The authors did not find any gender differences in any experiments.

Next, the authors tested the hypothesis about the unskilled that “the same incompetence that leads them to make wrong choices also deprives them of the savvy necessary to recognize competence, be it their own or anyone else’s” (p. 1126). And they did that by having both the competents and the incompetents see the answers that their peers gave at the tests. Indeed, the incompetents not only failed to recognize competence, but they continued to believe they performed very well in the face of contrary evidence. In contrast, the competents adjusted their ratings after seeing their peer’s performance, so they did not underestimate themselves anymore. In other words, the competents learned from seeing other’s mistakes, but the incompetents did not.

Based on this data, Kruger & Dunning (1999) argue that the incompetents are so because they lack the skills to recognize competence and error in them or others (jargon: lack of metacognitive skills). Whereas the competents overestimate themselves because they assume everybody does as well as they did, but when shown the evidence that other people performed poorly, they become accurate in their self-evaluations (jargon: the false consensus effect, a.k.a the social-projection error).

So, the obvious implication is: if incompetents learn to recognize competence, does that also translate into them becoming more competent? The last experiment in the paper attempted to answer just that. The authors got 70 students to complete a short (10 min) logical reasoning improving session and 70 students did something unrelated for 10 min. The data showed that the trained students not only improved their self-assessments (still showing superiority illusion though), but they also improved their performance. Yeays all around, all is not lost, there is hope left in the world!

This is an extremely easy read. I totally recommend it to non-specialists. Compare Kruger & Dunning (1999) with Pennycook et al. (2017): they both talk about the same subject and they both are redoubtable personages in their fields. But while the former is a pleasant leisurely read, the latter lacks mundane operationalizations and requires serious familiarization with the literature and its jargon.

Since Kruger & Dunning (1999) is under the paywall of the infamous APA website (infamous because they don’t even let you see the abstract and even with institutional access is difficult to extract the papers out of them, as if they own the darn things!), write to me at scientiaportal@gmail.com specifying that you need it for educational purposes and promise not to distribute it for financial gain, and thou shalt have its .pdf. As always. Do not, under any circumstance, use a sci-hub server to obtain this paper illegally! Actually, follow me on Twitter @Neuronicus to find out exactly which servers to avoid.

REFERENCES:

1) Kruger J, & Dunning D. (Dec. 1999). Unskilled and unaware of it: how difficulties in recognizing one’s own incompetence lead to inflated self-assessments. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 77(6):1121-1134. PMID: 10626367. ARTICLE

2) Russell, B. (1931-1935). “The Triumph of Stupidity” (10 May 1933), p. 28, in Mortals and Others: American Essays, vol. 2, published in 1998 by Routledge, London and New York, ISBN 0415178665. FREE FULLTEXT By GoogleBooks | FREE FULLTEXT of ‘The Triumph of Stupidity”

P.S. I personally liked this example from the paper for illustrating what lack of metacognitive skills means:

“The skills that enable one to construct a grammatical sentence are the same skills necessary to recognize a grammatical sentence, and thus are the same skills necessary to determine if a grammatical mistake has been made. In short, the same knowledge that underlies the ability to produce correct judgment is also the knowledge that underlies the ability to recognize correct judgment. To lack the former is to be deficient in the latter” (p. 1121-1122).

By Neuronicus, 10 January 2018