Following up on my promise to cover a few papers about self-deception, the second in the series is about the superiority illusion, another cognitive bias (the first was about depressive realism).

Yamada et al. (2013) sought to uncover the origins of the ubiquitous belief that oneself is “superior to average people along various dimensions, such as intelligence, cognitive ability, and possession of desirable traits” (p. 4363). The sad statistical truth is that MOST people are average; that’s the whole definitions of ‘average’, really… But most people think they are superior to others, a.k.a. the ‘above-average effect’.

Twenty-four young males underwent resting-state fMRI and PET scanning. The first scanner is of the magnetic resonance type and tracks where you have most of the blood going in the brain at any particular moment. More blood flow to a region is interpreted as that region being active at that moment.

The word ‘functional’ means that the subject is performing a task while in the scanner and the resultant brain image is correspondent to what the brain is doing at that particular moment in time. On the other hand, ‘resting-state’ means that the individual did not do any task in the scanner, s/he just sat nice and still on the warm pads listening to the various clicks, clacks, bangs & beeps of the scanner. The subjects were instructed to rest with their eyes open. Good instruction, given than many subjects fall asleep in resting state MRI studies, even in the terrible racket that the coils make that sometimes can reach 125 Db. Let me explain: an MRI is a machine that generates a huge magnetic field (60,000 times stronger than Earth’s!) by shooting rapid pulses of electricity through a coiled wire, called gradient coil. These pulses of electricity or, in other words, the rapid on-off switchings of the electrical current make the gradient coil vibrate very loudly.

A PET scanner functions on a different principle. The subject receives a shot of a radioactive substance (called tracer) and the machine tracks its movement through the subject’s body. In this experiment’s case, the tracer was raclopride, a D2 dopamine receptor antagonist.

The behavioral data (meaning the answers to the questionnaires) showed that, curiously, the superiority illusion belief was not correlated with anxiety or self-esteem scores, but, not curiously, it was negatively correlated with helplessness, a measure of depression. Makes sense, especially from the view of depressive realism.

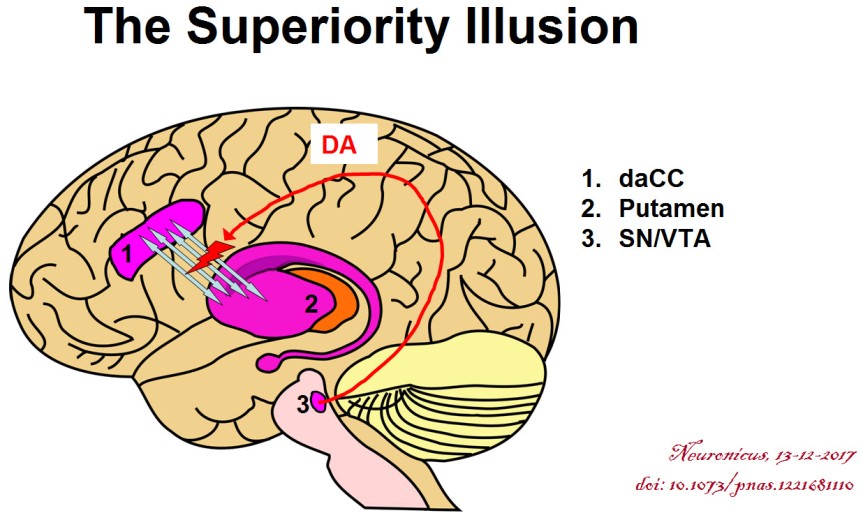

The imaging data suggests that dopamine binding to its striatal D2 receptors attenuate the functional connectivity between the left sensoriomotor striatum (SMST, a.k.a postcommissural putamen) and the dorsal anterior cingulate cortex (daCC). And this state of affairs gives rise to the superiority illusion (see Fig. 1).

This was a frustrating paper. I cannot tell if it has methodological issues or is just poorly written. For instance, I have to assume that the dACC they’re talking about is bilateral and not ipsilateral to their SMST, meaning left. As a non-native English speaker myself I guess I should cut the authors a break for consistently misspelling ‘commissure’ or for other grammatical errors for fear of being accused of hypocrisy, but here you have it: it bugged me. Besides, mine is a blog and theirs is a published peer-reviewed paper. (Full Disclosure: I do get editorial help from native English speakers when I publish for real and, except for a few personal style quirks, I fully incorporate their suggestions). So a little editorial help would have gotten a long way to make the reading more pleasant. What else? Ah, the results are not clearly explained anywhere, it looks like the authors rely on obviousness, a bad move if you want to be understood by people slightly outside your field. From the first figure it looks like only 22 subjects out of 24 showed superiority illusion but the authors included 24 in the imaging analyses, or so it seems. The subjects were 23.5 +/- 4.4 years, meaning that not all subjects had the frontal regions of the brain fully developed: there are clear anatomical and functional differences between a 19 year old and a 27 year old.

I’m not saying it is a bad paper because I have covered bad papers; I’m saying it was frustrating to read it and it took me a while to figure out some things. Honestly, I shouldn’t even have covered it, but I spent some precious time going through it and its supplementals, what with me not being an imaging dude, so I said the hell with it, I’ll finish it; so here you have it :).

By Neuronicus, 13 December 2017

REFERENCE: Yamada M, Uddin LQ, Takahashi H, Kimura Y, Takahata K, Kousa R, Ikoma Y, Eguchi Y, Takano H, Ito H, Higuchi M, Suhara T (12 Mar 2013). Superiority illusion arises from resting-state brain networks modulated by dopamine. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 110(11):4363-4367. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1221681110. ARTICLE | FREE FULLTEXT PDF