During the first week of the publication, a Cell paper that I covered a couple of weeks ago has received a lot of attention from media outlets, like The Atlantic, Scicasts and Neuroscience News/University of Utah Press Release. It is not my intention to duplicate here their wonderfully done summaries and interviews; rather to provide answers to some geeky questions arisen from the minds of nerdy scientists like me.

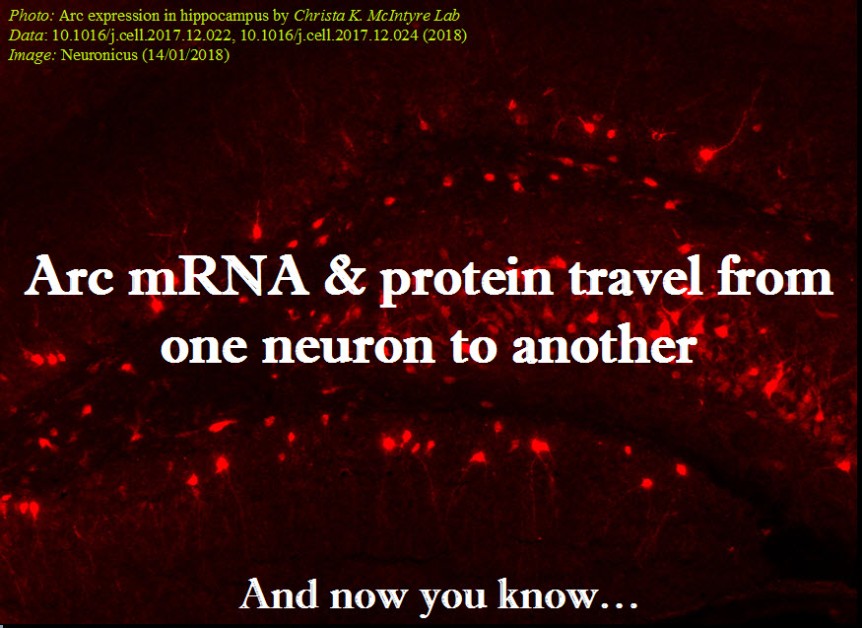

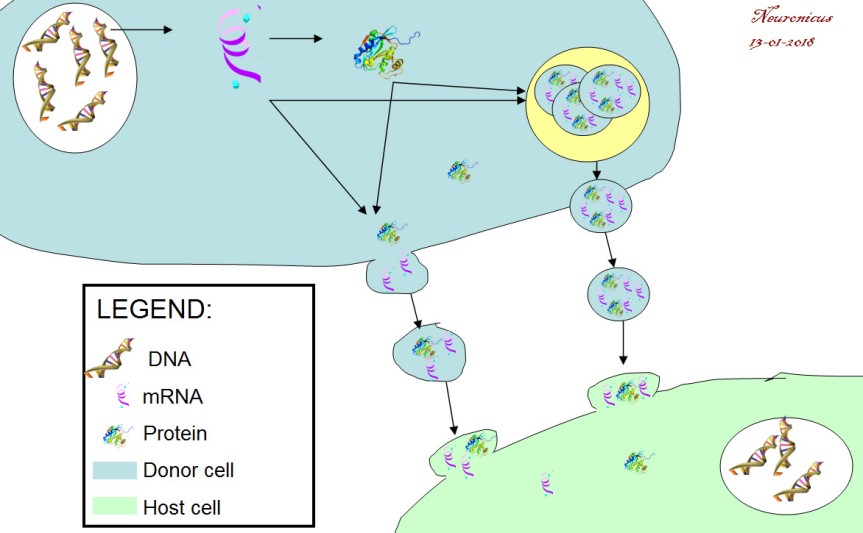

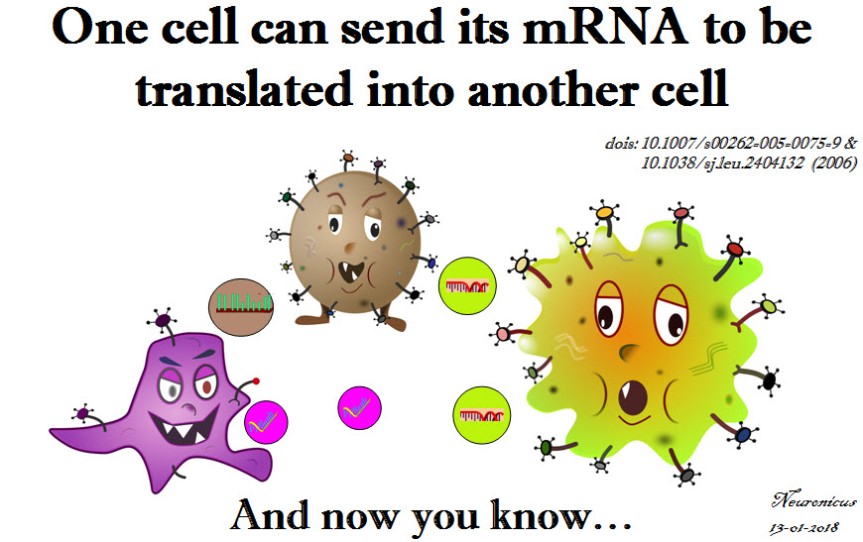

Dr. Shepherd, you are the corresponding author of a paper published on Jan. 11 in Cell about a protein heavily involved in memory formation, called Arc. Your team and another team from University of Massachusetts, who published in the same issue of Cell, simultaneously discovered that Arc looks like and behaves like a virus. The protein “infects” nearby cells, in this case neurons, with instructions of how to make more of itself, i.e. it shuttles its own mRNA from one cell to another.

Neuronicus: Why is this discovery so important?

Jason D. Shepherd: I think there’s a couple of big implications of this work:

-

The so called “junk” DNA in our genomes that come from viruses and transposable elements actually provide source material for new genes. Arc isn’t the first example, but it’s the first prominent brain gene to have these kinds of origins.

-

This is the first demonstration that cellular proteins are capable of assembling into capsid-like structures. This is a completely new way of thinking about communication between cells.

-

We think there may be other genes that can also form capsids, suggesting this method of signaling is fairly common in organisms.

N: 2) When you and your colleagues compared Arc’s genetic sequence across species you concluded Arc comes from a virus that infected four-legged animals some time ago. A little time later the virus infected the flies too. When did these events occur?

JDS: So we think the origins are from a retrotransposon not a virus. These are DNA sequences or elements that “jump” into the host genome. Think of them as primitive viruses. Indeed, these elements are thought to be the ancestors of retroviruses like HIV. The mammalian Arc gene seems to have originated ~400 million years ago, the fly about 150 million years ago.

N: 3) So, if Arc has been so successfully repurposed by the tetrapod and fly ancestors to add memory formation, what does that mean for the animals and insects before the infection? I understand that we move now in the realm of speculation, but who better to speculate on these things than the people who work on Arc? The question is: did these pre-infection creatures have bad and short memories? The alternate view would be that they had similar memory abilities due to a different mechanism that was replaced by Arc. Which one do you think is more likely?

JDS: Good question. It’s certainly the case that memory capacity improved in tetrapods, but unclear if Arc is the sole reason. I suspect that Arc confers some unique aspects to brains, otherwise it would not have been so conserved after the initial insertion event, but I also think there are probably other Arc-like genes in other organisms that do not have Arc. I will also note that we are not even sure, yet, that the fly Arc is important for fly memory/learning.

N: 4) Remaining in the realm of speculation, if this intercellular mRNA transport proves to be ubiquitous for a variety of mRNAs, what does that say of the transcriptome of a cell at any given time? From a practical point of view, a cell is what is made off, meaning the ensemble of all its enzymes and proteins and so on, collectively termed transcriptome. So if a cell can just alter its neighbor’s transcriptome array, does that mean that it’s possible to alter also its function? Even more outrageously speculative, perhaps even its type? Can we make cancer cells commit suicide by shooting Arc capsules of mRNA at them?

JDS: Yes! Cool ideas. I think this is quite likely, that these signaling extracellular vesicles can dramatically alter the state of a cell. We are obviously looking into this.

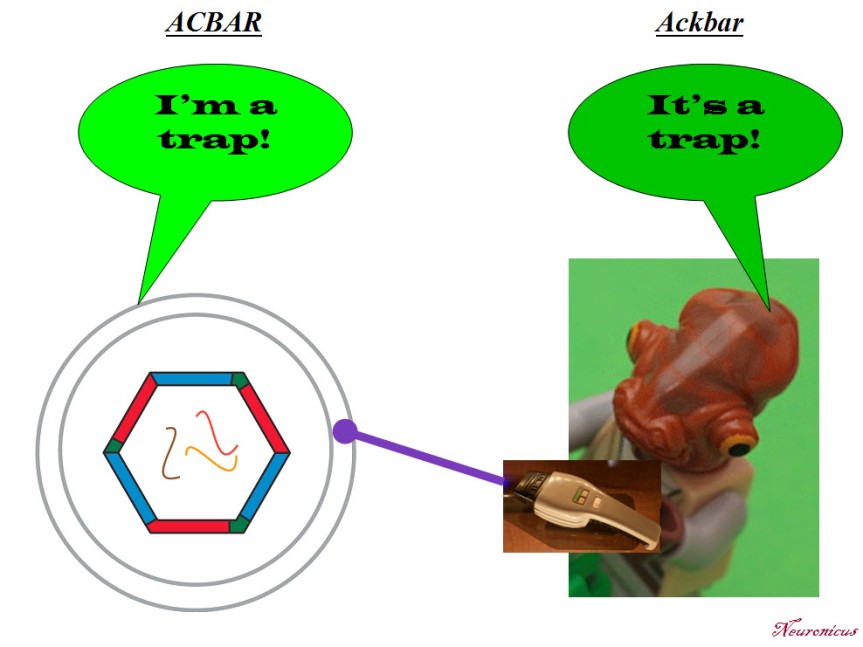

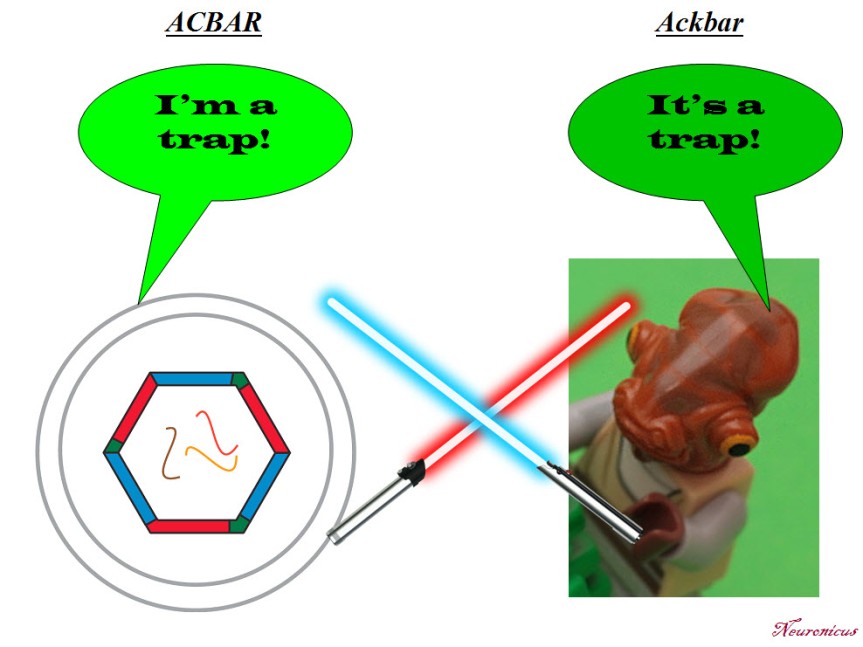

N: 5) Finally, in the paper, the Arc capsules containing mRNA are referred to as ACBAR (Arc Capsid Bearing Any RNA). At first I thought it was a reference to “Allahu akbar” which is Arabic for ‘God is greatest’, the allusion being “ACBAR! Our exosome is the greatest!” or “Arc Acbar! Our Arc is the greatest!”. Is this where the naming is coming from?

JDS: No no. As I said on twitter, my lab came up with this acronym because we are all Star Wars nerds and the classic “It’s a trap!” line from general Ackbar seemed apt for something that was trapping RNA.

Below is the Twitter exchange Dr. Shepherd refers to:

Dr. Shepherd, thank you for your time! And congratulations on a well done paper and a well told story. Your Methods section is absolutely great; anybody can follow the instructions and replicate your data. Somebody in your lab must have kept great records. Congratulations again!

By Neuronicus, 28 January 2018

P. S. Since I have obviously managed to annoy the #StarWars universe and twitterverse because I depicted General Ackbar using a Jedi sword when he’s not a Jedi, I thought only fair to annoy the other half of the world, the #trekkies. So here you go: