As most children, growing up I showed little appreciation for what I had, coveting instead what I did not. Now I realize how fortunate I have been to have grown up half the time in a metropolis and the other half at the countryside. At the farm. A subsistence farm, although I truly loathe the term because we were not just subsisting but thriving off the land, as we planted and harvested a bit of everything and we had a specimen or four of almost all the farm animals, from bipeds to quadrupeds.

I got on this memory lane after reading the paper of Shinozaki et al. (2018) on tomatoes. It was a difficult read for me as it was punctured by many term definition lookups since botany evolved quite steeply since the last time I checked, about 25 years or so.

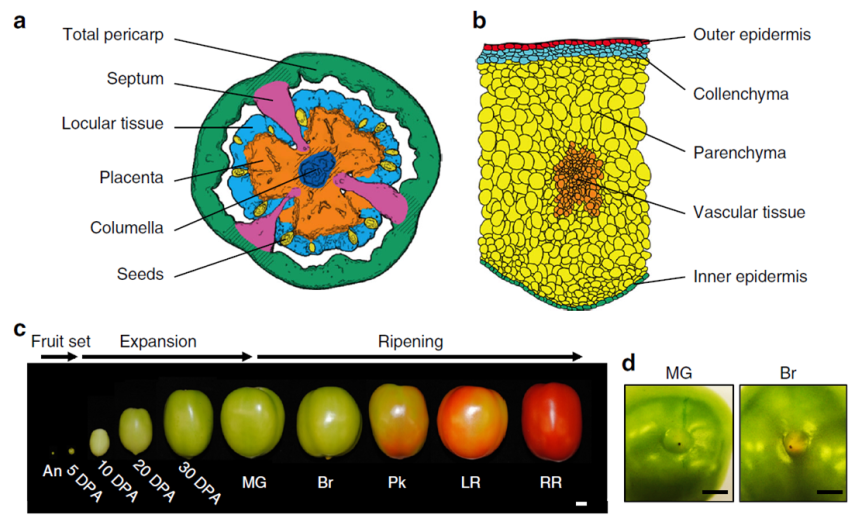

Briefly, the scientists grew tomato plants in a greenhouse at Cornell, NY. They harvested the fruit from 60 plants about 5 to 50 days after the flower was at its peak (DPA, days post anthesis) following this chart:

- Expanding [fruit] stage (harvested at 5, 10, 20, or 30 DPA)

- Mature Green stage (full-size green fruit, ≈ 39 DPA),

- Breaker stage (definite break in color from green to tannish-yellow with less than 10% of the surface, ≈ 42 DPA),

- Pink stage (50% pink or red color, ≈ 44 DPA),

- Light red stage (100% light red, ≈ 46 DPA),

- Red ripe stage (full red for 8 days, ≈ 50 DPA).

(simplified from the Methods section, p. 10, see pic)

Immediately after harvesting, the tomato was scanned with a micro-computed tomograph (micro-CT) to generate a 3D image of the fruit, including its internal structures. Then, the fruit was dissected by hand or laser, depending of its size, divided into various tissue types and then preserved either via snap-freezing in liquid nitrogen or standard tissue fixation for light or transmission electron microscopy. Finally, the researchers used kits to extract and analyze the RNA from their samples. And, last but not least, a lot of math & stats.

This is what I got out of it:

- A total of 24,660 genes were uniquely expressed in various tomato cell types and at various stages of development.

- The tomato ripens from within, meaning from the interior to the exterior and not the other way around.

- The ripening seems to be a continuous process, starting before the ‘Breaker’ stage.

- The ripening signals originate in the locular tissues (the goo around the seeds; it’s possible that the seeds themselves send the signals to the locular tissue to start the ripening process).

- The flesh of the fruit is only one part of the tomato and the most investigated, but the other types of tissue are also important. For example, some genes responsible for aroma and flavor (CTOMT1, TOMLOXC) are predominantly or even exclusively expressed in the flesh, but some genes that improve the nutritional value (SlGAD3) are expressed mostly in the placenta.

- The fruit can do photosynthesis, probably for the benefit of its seeds.

- Each developmental stage is characterized by a distinct transcriptome profile (by inference, also a distinct proteomic profile, although not necessarily in exact correspondence)

- Botany, like any serious science, is complicated.

Ah, I have been vindicated. By science, nonetheless! You see, in my pursuit to recapture the tomato taste of my childhood I sample various homegrown exemplars of Solanum lycopersicum derived both from more or less failed personal attempts with pots on the balcony and from various farmer’s market vendors. While I can understand – though not approve of – the industrial scale agro-growers’ practice to pick the tomatoes green, unripe and then artificially injecting them with ethylene to prolong shelf life, I completely fail to understand the picking them up when green by the sellers in the farmer’s markets. I had many surreal conversations with such vendors (I cannot call them farmers for the life of me) who more than once attempted to reassure me that 1) Everybody’s picking tomatoes green off the vine because that’s how it’s done and 2) Ripening happens on the window sill. In vain have I tried to explain the difference between ripen and rotten; in vain have I pointed out that color is only one indicator of ripening; in vain did I explain that during ripening on the vine the plant delivers certain substances to the fruit that lead to changes in the flesh composition to make it more nutritious for the future seedling, process that the aforesaid window sill does nor partake in. Alas, ultimately, my arguments (and my family’s last 400 years of farming experience) hit the wall of “I am growing tomatoes for three years now and I know what I’m doing. Are you buying or not?” As you might imagine, I end up going home frustrated and yet staring at some exorbitantly expensive and looking as sad as I feel greenish tomatoes.

For me, this is what Shinozaki et al. (2018) validated: Ripening is a complex process that involves a lot of physiological changes in the fruit, not merely some extra production of ethylene that can be conveniently supplied externally by a syringe or rotting on the window sill. Of course, there is nowhere in the paper that Shinozaki et al. (2018) say that. What they do say is this: “The ripening program is revealed as comprising gradients of gene expression, initiating in internal tissues then radiating outward, and basipetally along a latitudinal axis. We also identify spatial variations in the patterns of epigenetic control superimposed on ripening gradients” (Abstract). Tomayto, tomahto…

Now we know that… simply put, I’m right. Sometimes is good to be right. I am old enough to prefer happiness and tranquility over rightness & righteousness, but still young enough that sometimes, just sometimes, it feels good to be right. Yes, the Shinozaki et al. (2018) paper exists only for my vindication in my farmer’s market squabbles and not for providing a huge comprehensive atlas on the tomato transcriptome, along with an awesome spatiotemporal map showing the place and time of the expression of genes responsible for fruit ripening, quality traits and so on.

Good job, Shinozaki et al. (2018)!

REFERENCE: Shinozaki Y, Nicolas P, Fernandez-Pozo N, Ma Q, Evanich DJ, Shi Y, Xu Y, Zheng Y, Snyder SI, Martin LBB, Ruiz-May E, Thannhauser TW, Chen K, Domozych DS, Catalá C, Fei Z, Mueller LA, Giovannoni JJ, & Rose JKC (25 Jan 2018). High-resolution spatiotemporal transcriptome mapping of tomato fruit development and ripening. Nature Communications, 9(1):364. PMID: 29371663, PMCID: PMC5785480, DOI: 10.1038/s41467-017-02782-9. ARTICLE | FREE FULLTEXT PDF | The Tomato Expression Atlas database

By Neuronicus, 7 February 2018